The Loneliness Epidemic: How Social Isolation is Taking Lives10 min read

What’s worse for your health, complete physical inactivity or having no social connections? The answer might surprise you.

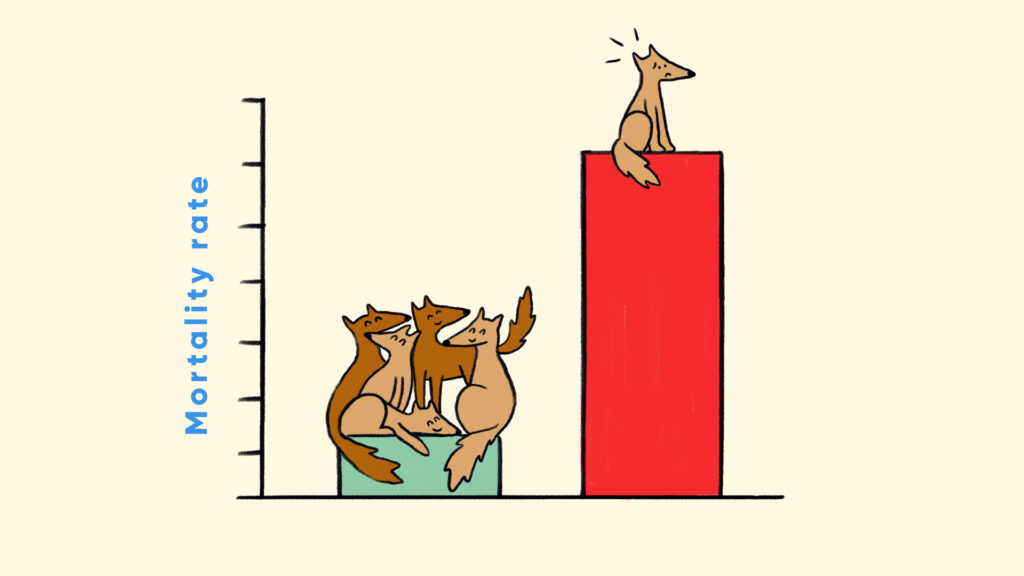

Longevity is determined by two things, genetics, and your environment. Social relationships are included in the environment and are something we, as humans, have relied on for thousands of years. Historically, human communities depended on each other for meat-sharing, protection against predation, and communal child-rearing.11,12 If you leave the pack, you will die sooner. Compared to those who stay in the pack, coyotes that leave the pack has a higher mortality rate than their peers.13

The WHO has identified social exclusion as one of health’s ten critical social determinants.14 Here is a scary study result: lack of social connections, when factoring in multidimensional analysis, increases the odds of mortality by 91%.15,16 The mortality risk from social exclusion is comparable to smoking and more significant than the mortality risk from obesity or physical inactivity.16,17

Benefits of Social Relationships

What if solid community ties can fight off disease, crime, alcoholism, and suicide? In the late 19th century, hundreds of immigrants from Roseto, Italy, established a new home in Pennsylvania they called “Roseto.” Imagine taking your entire extended family and friends and creating a neighborhood of only those people. Now, this may be enjoyable, but what if it made you live longer? Researchers and physicians became interested in the new town of Roseto, Pennsylvania, as no one under 55 showed any signs of heart disease, which was a stark difference when compared to the rest of men in the United States. Also, men over 65 in Roseto died from heart disease at a rate half that of the US population.

What was going on with these people? Interestingly, diet and exercise were no different from the average of the rest of the US population. The only environmental difference? The community. The effect was so strong that this health phenomenon was called “The Roseto Effect,” popularized by Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers.8

Where are the outliers in the rest of the world for longevity? Sardinia, Italy, is home to the world’s highest concentration of male centenarians, which is people who are 100 years or older.10 Around 1 in 600 Sardinians live to be 100 years or older. That’s about 7x better than the US, where only 1 in 4,000 live to or past 100 years old. Unlike the US, the older generation in Sardinia is revered, and family is paramount. Family and elder reverence is a common theme in Blue Zones worldwide, which are areas of the world where people most frequently live over 100 years old.9

One study, searching for associations and casualty between social relationships and health, looked at over 20,000 adolescents across 20 years and found that social integration relates to better physiological functioning and lower risks of physical disorders in a dose-response fashion.1 Individuals with a higher degree of social connectedness had a lower predicted value in CRP (a marker of inflammation), waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, and body mass index (figure 2).

Figure 2. Prospective associations of social integration with biomarkers of physiological functioning over the life course. Results based on ordinary least squares (OLS) models of biomarkers at follow-up regressed on baseline social integration, adjusting for age, sex, and race. HRS and NSHAP findings are similar, so we present the larger HRS sample results.1

The researchers developed a “Standardized Social Integration Scale,” which measures social exclusion or lack thereof, and that score came from questions such as, “How many friends do you have? Are you in contact with your parents? Do you attend religious gatherings? How close do you feel to your family? Do you feel supported by your family? Do you have close friends?” And so on.

The results indicate that scoring high on this questionnaire was associated with individuals living longer, but what about being socially excluded? Does social exclusion have an association with reduced health or lifespan?

The Negatives of Social Exclusion

One of the earliest known reports of banishment was in 487 BC with the banishment of Hipparchos, son of Charmos, from Athens. He was ostracized due to the suspicion that he supported the Tyrant Pesistratos. In ancient Greece, banishment was considered a punishment worse than death; it was considered the ultimate punishment.21 Today, banishment still exists and is still feared. There are groups of people named Nomadic Forager Band Societies (NFBS), which are modern-day examples of tribal societies that ostracize members.

NFBS are nomadic, small, egalitarian, and, most importantly, interdependent communities. Individuals in such societies are expected to be generous and cooperative. Neither bossy nor arrogant.18 One example of the value placed on community relationships is a description from a member of the Ju/’hoansi, an NFBS, of the African Kalahari, who describes the idea of a son-in-law “should be a good hunter; he should not have a reputation as a fighter. He should come from a friendly family of people who like to do ‘hxaro,’ the Ju/’hoan form of a traditional exchange.”19 In such tribes as these, ostracism is a death sentence. One example is the case of a man named Amechichi, a Montagnais-Naskapi man expelled from his community for continuously poaching on the hunting grounds of others. Oh yeah, his family was expelled with him. His expulsion caused rejection from several other hunting bands, at which point he withdrew into the woods, where he and his family died of starvation.18

However, social exclusion in the more common societies of the modern day still has detrimental effects. Social isolation in adolescence increased the risk of inflammation in humans by the same magnitude as physical inactivity, and social isolation association with hypertension exceeded that of clinical risk factors such as diabetes in people of older age. A lack of support or a high-strain relationship can create chronic stress, making individuals more prone to chronic disease, which reduces these individuals’ lifespans.1-4

Coming back to the original longitudinal study, which looked at over 20,000 adolescents across 20 years, the most significant results were the association between significantly elevated CRP and social isolation (OR = 1.27, P=0.05), and this was to a greater degree than physical inactivity (OR = 1.21, P=0.05). And an elevated CRP isn’t something to be ignored. Elevated CRP has been associated with various poor outcomes. For example, raised CRP levels to predict a worse outcome for patients with COPD.5 People with depression are more likely to have an elevated CRP than patients without it, a meta-analytic odds ratio comparing patients with depression to controls found an odds ratio of 1.47 (95% CI 1.18-1.82).6 Finally, elevated CRP predicts cardiovascular events in adults. Even in children, there are consequences. When children with non-detectable CRP are compared with children with elevated CRP, the children with elevated CRP levels are found to have early arterial changes such as intima-media thickening, possibly connecting CRP in the pathogenesis of early atherosclerosis.7

Final Thoughts

So, are we doomed? If we don’t have close friends, close family members, or a community we can turn to, will we live shorter lives? Judging from the evidence, our odds of dying sooner dramatically increase when socially excluded. What can we do?

The authors of the first paper have some suggestions. In adolescence, we should aim for a large and varied social network, as there is a dose-dependent relationship between social connectedness and cardiovascular health and metabolism. In midlife, relationship quality significantly impacts health more than quantity. Finally, in late life, broad social networks, as in quantity, overtake quality of connection again, with wider social networks strongly associated with decreased likelihoods of obesity and hypertension.1 Keep in mind many of these are associations and not causations, so take the statements with a grain of salt. My personal opinion is a few high-quality relationships are much more valuable than many low-quality relationships.

However, scientific evidence points towards a strong association between good social relationships and a longer lifespan. The coyote, hoping to live longer, must rejoin the pack. The exiled tribe member must beg forgiveness. Their longevity and health depend on being socially included. Members of modern-day communities also are not free from the physiological consequences of being socially excluded. Ok, maybe I should call my mom, or, wait, what if I just learned how to be a coyote?

Work Cited

- Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Jan 19;113(3):578-83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511085112. Epub 2016 Jan 4. PMID: 26729882; PMCID: PMC4725506.

- MJ Shanahan, Social genomics and the life course: Opportunities and challenges for multilevel population research. The Future of the Sociology of Aging: An Agenda for Action, ed L Waite (National Academies Press, Washington, DC), pp. 255–276 (2013).

- YC Yang, K Schorpp, KM Harris, Social support, social strain and inflammation: Evidence from a national longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Soc Sci Med 107, 124–135 (2014).

- Y Ben-Shlomo, D Kuh, A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 31, 285–293 (2002).

- Broekhuizen R, Wouters EF, Creutzberg EC, Schols AM. Raised CRP levels mark metabolic and functional impairment in advanced COPD. Thorax. 2006 Jan;61(1):17-22. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041996. Epub 2005 Jul 29. PMID: 16055618; PMCID: PMC2080712.

- Osimo EF, Baxter LJ, Lewis G, Jones PB, Khandaker GM. Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP levels. Psychol Med. 2019 Sep;49(12):1958-1970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001454. Epub 2019 Jul 1. PMID: 31258105; PMCID: PMC6712955.

- Järvisalo MJ, Harmoinen A, Hakanen M, Paakkunainen U, Viikari J, Hartiala J, Lehtimäki T, Simell O, Raitakari OT. Elevated serum C-reactive protein levels and early arterial changes in healthy children. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002 Aug 1;22(8):1323-8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000024222.06463.21. PMID: 12171795.

- Gladwell, Malcolm. Outliers. Back Bay Books, 2009.

- Blue zones

- Nieddu A, Vindas L, Errigo A, Vindas J, Pes GM, Dore MP. Dietary Habits, Anthropometric Features and Daily Performance in Two Independent Long-Lived Populations from Nicoya peninsula (Costa Rica) and Ogliastra (Sardinia). Nutrients. 2020 Jun 1;12(6):1621. doi: 10.3390/nu12061621. PMID: 32492804; PMCID: PMC7352961.

- Hawkes, Kristen, James F. O’Connell, and NG Blurton Jones. “Hadza meat sharing.” Evolution and Human Behavior 22.2 (2001): 113-142.

- HeavyRunner, Iris, and Joann Sebastian Morris. “Traditional Native culture and resilience.” (1997).

- Bekoff, M., & Wells, M. C. (1982). Behavioral ecology of coyotes: Social organization, rearing patterns, space use, and resource defense. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 60(4), 281–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1982.tb01087.x

- https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- MG Marmot, Status syndrome: A challenge to medicine. JAMA295, 1304–1307 (2006).

- J Holt-Lunstad, TB Smith, JB Layton, Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7, e1000316 (2010).

- JS House, KR Landis, D Umberson, Social relationships and health. Science 241, 540–545 (1988).

- Söderberg, Patrik, and Douglas P. Fry. “Anthropological aspects of ostracism.” Ostracism, exclusion, and rejection. Routledge, 2016. 268-282.

- Wiessner PW. Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Sep 30;111(39):14027-35. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404212111. Epub 2014 Sep 22. PMID: 25246574; PMCID: PMC4191796.

- William Smith (1890), “Banishment (Roman)”, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (3rd ed.), pp. 136–137

- The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, First Edition. Edited by Roger S. Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine, and Sabine R. Huebner, print page 3223.

© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published 2013 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

DOI: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah04132

0 Comments