The 8 Most Important Study Techniques I use in Medical School17 min read

For the past two years, I have studied more than I have in my entire life. At least one-third of every day has been studying. I study at least 8 hours a day, 6 days a week. That equates to about 5000 hours, which is over 200 full days, of studying in the past two years.

If I am spending this much time of my life studying, I should use this time as efficiently as possible. Over my past 9 years in higher education, I have found 8 techniques that maximize my results from time spent studying; the techniques that really work. Here are my favorite study techniques that help me study more effectively and efficiently. I also include the tools and apps I use to help maximize results from these techniques.

As a prerequisite, the things you do before studying is vital. I have a post here on how to best prepare for studying before you even open a book or your laptop. Very briefly these are: get a good night’s sleep, exercise, have a clean space, and mentally prepare.

1. Pomodoro Method

The Pomodoro method is studying for a set amount of time and then taking a break for a set amount of time. This is a procrastination buster that makes the work less intimidating because it breaks it into small clumps. Also, because you know you will be studying during this time and only studying, it makes it easier to ignore distractions. The most common strategy is:

- Set a 25 Minute Timer

- Study and ONLY Study during that time

- Break for 5 Minutes

- Repeat the above “Pomodoro” session four times

- After the 4th Pomodoro take a 15-30 minute break instead of a 5-minute break.

So one “block” might look something like this:

- 25 minutes study

- 5-minute break

- 25-minute study

- 5-minute break

- 25 minutes study

- 5-minute break

- 25 minutes study

- 30-minute break

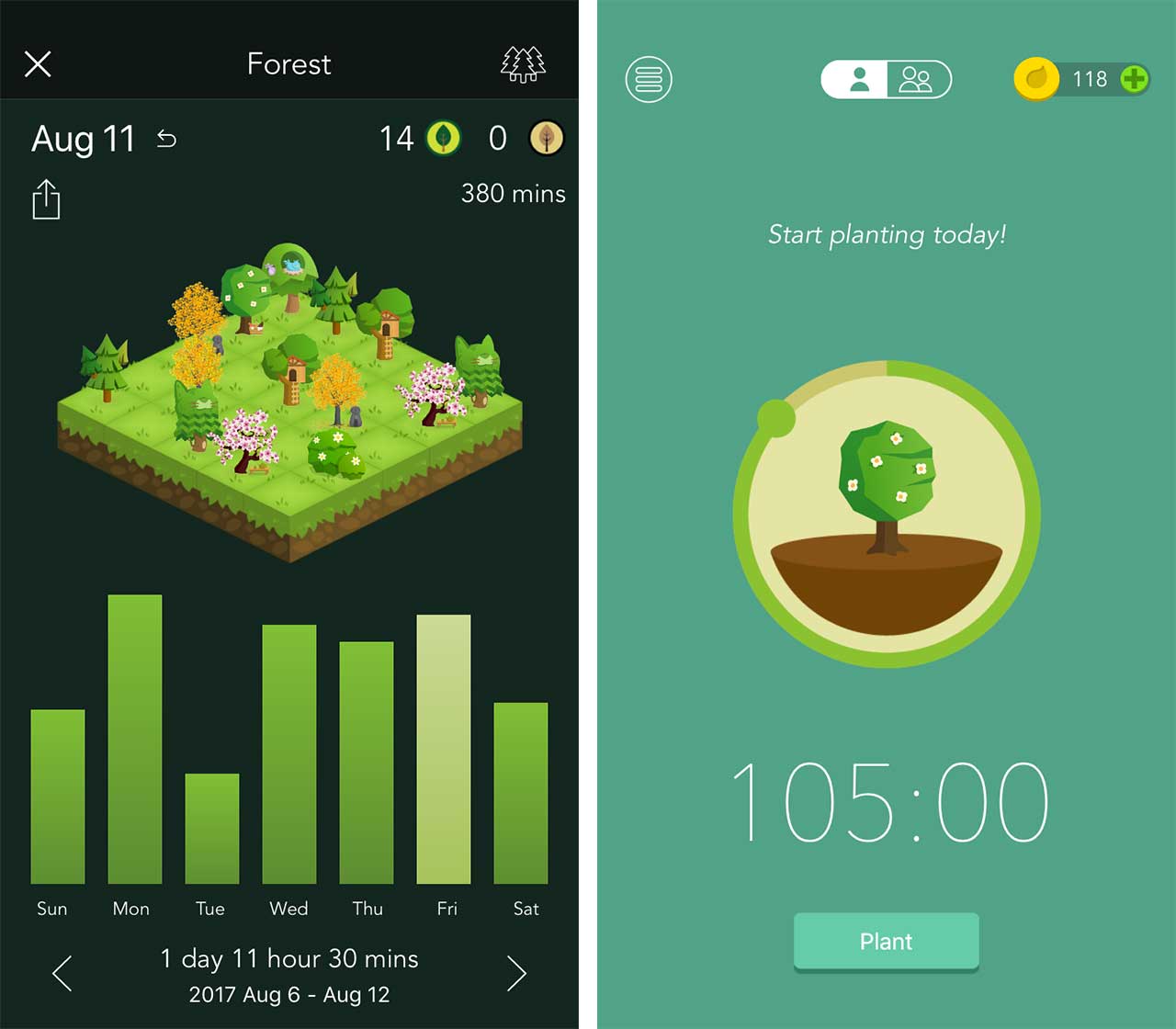

Another great thing about this method is that you can gamify it (which, research shows, improves performance)1. I like to aim for at least ten Pomodoro sessions a day and, with certain apps like Forest, you can visually track your performance and compete with friends.

The most important thing is to only study during study time. If you begin to slack off during those study times you are defeating the entire purpose of this method. Save your slacking for the 5-minute breaks.

What to do on your breaks: Anything you want! Personally, I think it’s best to do something that doesn’t include a screen and isn’t seated. Some options:

- A short walk outside (my favorite option)

- Clean Desk / Apartment (my second favorite option)

- Play an instrument (my third favorite option)

- Watch a YouTube video or browse the internet laying down on the floor (what I often end up doing)

- Talk with friends/family

- Grab and eat a snack

- Do some pushups or bodyweight exercises

Tools:

- Forest Timer (iPhone app) – Every completed session is a new tree; option to study real-time with friends.

- Be Focused – Focus Timer (Mac app) – Minimal, adjustable, Pomodoro App (The one I use).

- Self Control (Mac app, try cold turkey for windows) – Timer that once you set, will block access to whatever you want. Deleting the application or restarting your computer still won’t allow you access to those places on the internet.

Caveats

- Some people prefer 50/10 Pomodoro’s or other time-mashups. It really doesn’t matter just keep a “rate” of for every 10 minutes of work you will take a 2-minute break. So if you studied for 60 minutes you would take a 12-minute break.

- This will only be an effective technique if you make it an effective technique, only study in these study time intervals. Otherwise, you will hamper your mental fortitude and reduce any possible benefits you may gain from classical conditioning.

Bottom Line: Study in study/break increments. The one I like is 25/5, 25/5 25/5, 25/30, and repeat. Another popular increment is 50/10, 50/10, 50/30,

2. Feynman Technique

If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.

Albert Einstein

Richard Feynman was a renowned physicist and teacher. Albert Einstein and Bill Gates were both students of Feynman’s amazing lectures. Richard Feynman emphasized the importance of explaining complex ideas simply. The Feynman technique is exactly that, can you explain the piece of information you just learned simply? Would a child understand you? Here’s me using the Feynman Technique to explain the Feynman Technique:

- Identify the information, what material did you just learn?

- How would you teach it? Imagine explaining this information to a friend who is clueless. Avoid jargon, prioritize brevity.

- Did you find anything difficult to explain? Do a little more studying, rework that information in your head, how can you make it simple and understandable?

- Try teaching it again. Most people do it mentally but talking out loud works as well.

Let’s try an example from the master himself, explaining inertia:

…if an object is left alone, is not disturbed, it continues to move with a constant velocity in a straight line as if it was originally moving, or it continues to stand still if it was just standing still.2

Richard Feynman

If I were to try and explain something like diabetes, for example, I would do it something like this:

When you eat your morning bowl of cereal there is sugar in that bowl. Now you will need some of that sugar, to get up and walk to wherever you are going, but you won’t need all of it. So what does your body do with that leftover sugar? Your body says, “hmm I think I’d like to keep that sugar in case I might need it to do other things later! Like run! or jump!” That’s where insulin comes in. Insulin allows you to “store” this sugar away for later. In diabetes, however, your insulin isn’t working as well or you don’t have insulin. So you can’t “store” your leftover sugar because that’s what insulin does. So, when you need sugar but haven’t just eaten, your body can’t access these “stores” of sugar because insulin wasn’t there to store the sugar for later. So someone with diabetes may get sick if they wait too long after not eating because they can’t don’t have any sugar to help them move and for their brain to work right. (This is, of course, an extreme oversimplification, but I think a 5-year old might understand this? Don’t you?)

The way to get the most out of this technique is to take it seriously and use it consistently. Actually, imagine you were with your friends and they were asking you to explain this topic. For example, as I’m doing my flashcards, I like to think one of my friends is asking me the question and then asks “why?” This keeps me on my toes and keeps me honest. It also helps avoid the trap of memorization instead of understanding.

Then I may write my “teaching” into my flashcard.

Tools:

- Phone (yes your phone) – call your friend, who knows nothing about what you are learning, and try to explain what you just learned. Can you explain it so they understand?

Bottom Line: Try and imagine explaining what you just studied to a child and then do that (in your head or out loud).

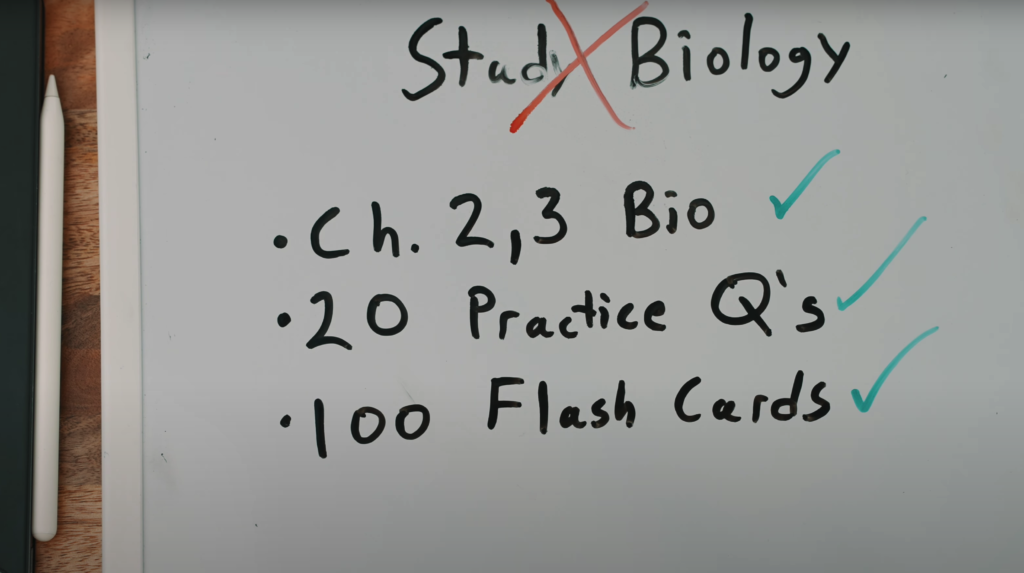

3. Avoid Highlighting, Rereading, and Summarizing

I have an entire post on this here. Evidence shows summarizing, highlighting, and rereading are poor techniques when it comes to retaining information. Active recall and practice testing have been shown to be significantly better in regards to improving content retention.

When I cut out these methods and integrated the following methods my exam scores went up and my stress went down.

Tools

- Furnace for your highlighters

Bottom line: Avoid highlighting, rereading, and summarizing at all costs.

4. Practice Testing / Active Recall

The evidence shows those other techniques don’t work, so what do we do? What does the evidence support? Well, the following three techniques are backed by evidence and my personal experience.

Practice testing and active recall are pillars one and two of my most important three pillars to studying.

Practice testing is exactly that, doing practice problems that mimic as closely as possible what you will see on test day.

Active recall is when you have to work to recall something. When I ask you, “What is 2+2?” You have to think about that. That’s active recall. Active recall, or active learning, is different from passive learning. When you read “2+2=4” that is passive learning.

Your brain is working harder, and you are learning more, from “What is 2+2?” If you take someone and put them in the gym for six months, three months in condition “A”, and three months in condition “B”, which of the following two conditions do you think will make them stronger more quickly?

A. Have them watch bodybuilders lift weights for 3 months

B. Have them lift weights for 3 months.

Now, this is an oversimplification, and probably a bad metaphor, but I think the same thing applies to passive vs. active learning. When you are doing a tough problem you feel your brain working, now compare that feeling to the effort it takes to read this right now?

Isn’t reading this easier than the homework you just completed? The essay you wrote? The practice problems you just did? The Test you just took?

See what I mean?

Tools:

- Teacher’s practice questions

- Anki

- My 9-day Exam Prep Rongie Method

- Online question banks (Quizlet, Khan Academy, subject-specific websites)

Bottom Line: Use active recall and practice testing as much as you can when studying.

5. Spaced Repetition

I don’t think it’s possible to go a single post without talking about Anki, so I won’t! Just as every action has an equal and opposite reaction, Zach will talk about Anki.

My main post on spaced repetition is here. All spaced repetition is learning at intervals. So if you go to class and learn about topic A on Monday and then you review topic A on Tuesday, and then again on Friday, that is spaced repetition.

The amazing thing about Anki is that it spaces out our learning to take advantage of this forgetting curve. Anki will test you right before you fall off of the forgetting curve.

Now just apply that to everything you learn. Seriously. It’s what the evidence supports, it’s what the top-performing students at my medical school, and it’s what I do.

Tools

Bottom Line: Use Anki to integrate spaced repetition into everything you learn.

6. Make Connections (Hebbian Theory)

The more connections we make to other topics the more likely we are to retain that information. Now, this isn’t an exact science, it’s a theory, Hebbian theory.3,4

It’s a quite math-intensive and interesting theory, but the idea is basically as described above. We can connect our memories, and the more synaptic connections we have based on those memories, the “stronger” that memory is.

So how do I take advantage of this?

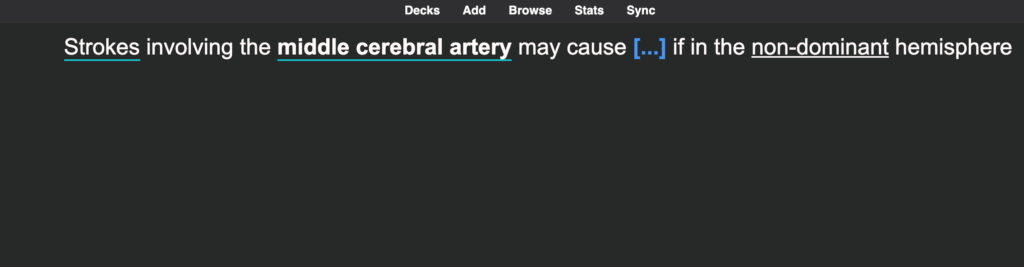

Well whenever I learn something, I try and make a connection to something else I have learned. Let’s take one of my flashcards, try and ignore the jargon, but this is something I need to know.

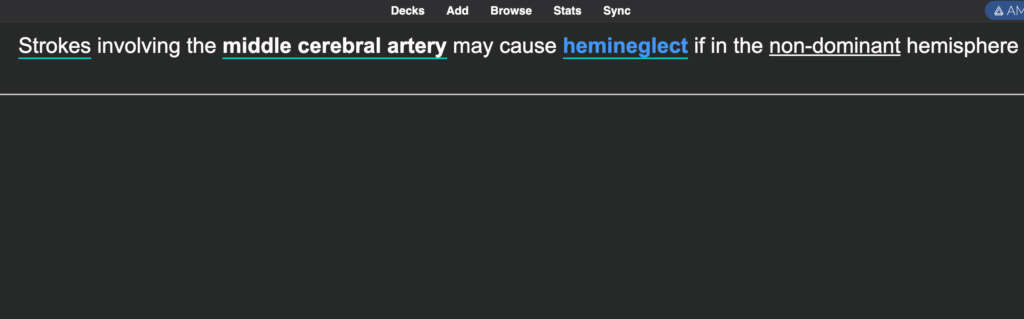

Hemineglect is when you are unaware of one side of your body/limb, a cerebral artery is an artery in your brain, a stroke is when the blood supply to a certain part of your brain is interrupted.

The answer that goes in the blank is “hemineglect.” Now I could stop there and be done with that flashcard. But I want to take advantage of Hebbian theory. I want to make as many connections as possible.

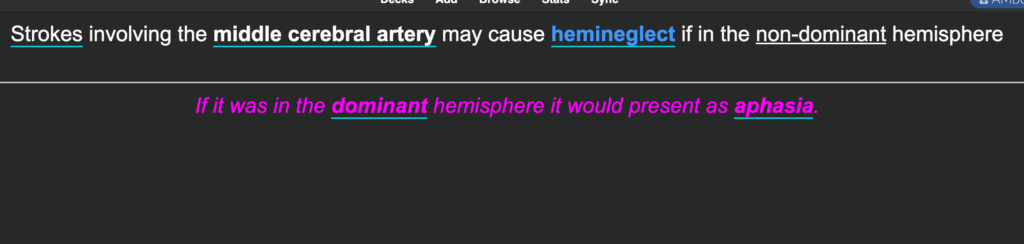

How can I take this card one step further?

Well, I also know you could get a stroke on the other, dominant, side of your brain. So if you got a stroke on the dominant side of your brain would you still have the same symptoms of hemineglect?

The answer is no, you wouldn’t. If it was a middle cerebral stroke in the dominant hemisphere you would present with symptoms of aphasia (or inability to understand/produce/use language).

So with a 2-second edit my new flashcard might look something like this:

Bam! Now I not only have this specific piece of information learned, but I have made a connection to another piece of information. Strengthening this memory and helping me keep another piece of information straight.

This method could also be called “chunking,” but we will go into that later.

Bottom Line: Make connections between facts and information you are learning, it will make the memory stick longer and make more sense.

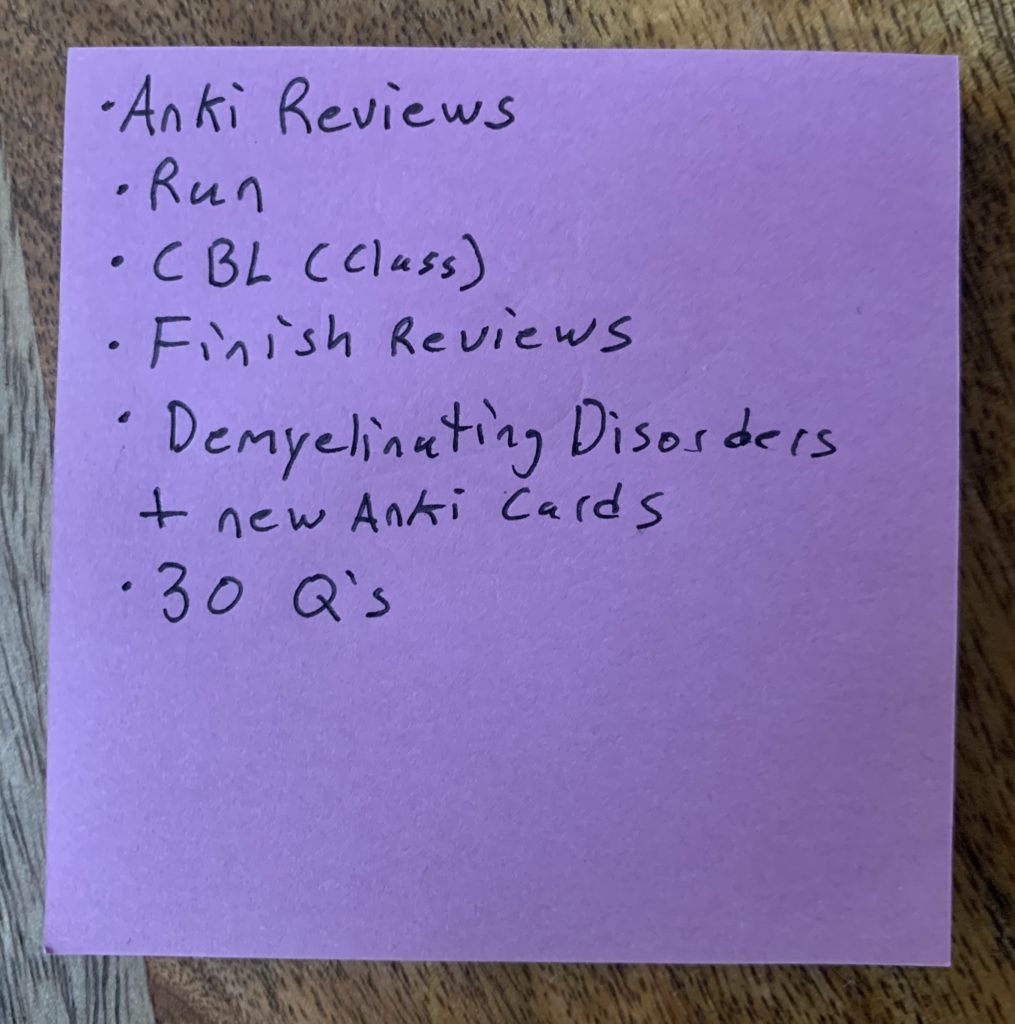

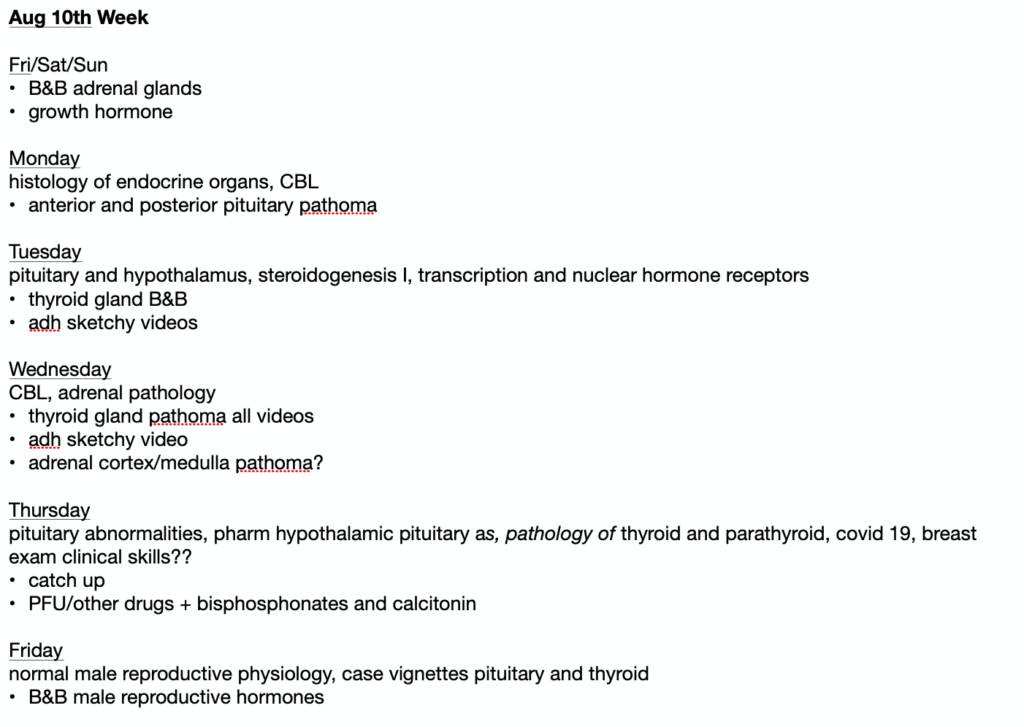

7. Planning

Planning removes stress from the next day, provides actionable goals, and allows me to jump right into whatever I need to do as soon as I wake up.

In general, the more specific the better. You want to know exactly what you will be doing before you start working.

I plan the next day every night on a post-it. This takes me 3 minutes and dramatically improves my focus and performance the next day. I think my post-its are getting bored of me writing “Anki Reviews” on them though…

I plan the next week every Sunday on a Notability file. Apologies, as the below document is messy. The bulleted points are my goals for the day and the non-bulleted points are my activities for the day.

For very large exams, like the MCAT or Step 1, I plan out my months.

For life and general things I use a hand-written notebook, calendar, or Notion.

Helpful Articles (Tools)

- My Daily Study Routine in Medical School

- How I take 0 Notes in Medical School

- How I prepare for exams in Medical school – 9 Day Plan + Rongie Method

Bottom Line: Try planning out your weeks the week before, and your days the day before. I usually do this Sunday night (for weeks) and before I go to bed (for weekdays).

8. Mnemonics Devices

These are specific tools that are used by the “memory champions” of the world because they work really, really well.

With all of this the more senses you can integrate (taste, smell, sight, sound) the better.

Also, usually, the more vulgar or funny the better (in my personal experience).

a. Memory Palace / Imagery

This is why Sketchy and Picmonic and other learning platforms are so popular for medical school. Memory palace/imagery techniques are such a good technique that world-class memory competitors use them to pull such feats as memorizing 483 digits in a string of random numbers in just 5 minutes. Amazingly, this same person who did that feat also memorized 3,029 numbers in just one hour.5

I think I can go as far as 3.1415 for pi…

But how does this work? Well, I want to create associations between what I am learning and a mental image. One way is the memory palace. If I picture my home, I can picture my bathroom, my bedroom, and my kitchen. Now I place objects I want to remember in those different rooms, for example, if I wanted to remember an apple, a soccer ball, and a printer I would think… An apple is sitting in the toilet, a soccer ball is where my pillow should be in the bedroom, and the printer is being lit on fire by my stove.

Now I just walk through my house in my head and I remember the printer is on fire, my pillow is a soccer ball, and there’s an apple in my toilet. Try this! It really does work.

Importantly, this doesn’t work with concepts, it only works with the specific information you need to learn (memorization). This is why Sketchy works so well for remembering different information about the different bacteria and viruses because it’s not really a concept I just need to know is if the bacteria are gram-positive or negative, which is indicated by the colors purple or red in the image. Is it encapsulated or naked, this is depicted by the presence of the (nude) statue of David or a character wearing a jacket.

b. Acronyms

One acronym I don’t think I will ever forget is ROY G BIV. The wavelengths of visible light to the human eye. R is red, and the lowest wavelength and V is violet, the highest wavelength. I think you can guess what’s in between.

An acronym is using the first letter of a group of words to form a different word that can be easily remembered.

Other popular acronyms are ones such as HOMES to remember the five Great Lakes:

- Huron

- Ontario

- Michigan

- Erie

- Superior

Or, for medical school, the one that comes to my mind is MUDPILES (for different causes of metabolic acidosis).

c. Acrostics

Acrostics are similar to acronyms, except it’s usually a sentence and the first letter of each word in that sentence means something to remember.

For example to remember the order of the planets you could say, “My Very Evil Mom Just Served Us Nachos.” (for Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune). I will not be debating the planets in this post.

To make it medical one acrostic to remember the branches of the external carotid artery is, “Some Anatomists Like F***ing Over Poor Medical Students.” For the superior thyroid artery, ascending pharyngeal artery, lingual artery, facial artery, occipital artery, posterior auricular artery, maxillary artery, superficial temporal artery.

d. Chunking

Finally, chunking is a tool that is used by Nuclear technicians and Military officers. That’s because it’s easier to remember, like your phone number right? You say it in three “chunks.” (If you live in America).

What is easier to look at: 2344830980 or 234-483-0980?

The latter right? and it’s easier to remember.

Importantly this can be applied to concepts. When you learn something try and connect it to other topics you have learned or will be learned. This will make it easier for that information to stick, I hope this helped!

-Zach

Conclusion

Certain study techniques are backed by research and will save you time, and increase your performance. Focus on the strategies that work and start scoring better.

Work Cited

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563215300868

- https://www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/I_09.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6212519/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/nn0900_919

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/this-man-memorized-a-shuffled-deck-of-cards-in-1865-seconds-heres-how/2016/05/16/c2ee85d4-15f1-11e6-aa55-670cabef46e0_story.html

2 Comments

How to Create an Effective Study Routine – Jenga Blogs · January 2, 2025 at 9:51 am

[…] Zach. (2021, May 9). The 8 Most Important Study Techniques I use in Medical School. Zach Highley. https://zhighley.com/the-8-most-important-study-techniques-i-use-in-medical-school/ […]

How to Create an Effective Study Routine – Life Byte Blogs · January 2, 2025 at 10:32 am

[…] Zach. (2021, May 9). The 8 Most Important Study Techniques I use in Medical School. Zach Highley. https://zhighley.com/the-8-most-important-study-techniques-i-use-in-medical-school/ […]