I remember my first notebook from 1st grade. It was a glorious, black, lined piece of stationery. It settled perfectly next to my pencil case inside my classy Jansport backpack. If only I knew how useless that notebook was. If only I knew that there were study strategies that took less time and were much more effective. If only I knew most study strategies we were taught in school were a waste of time.

In this post, I’ll go over the 8 biggest studying mistakes. Study methods I avoid at all costs.

1. Highlighting

Inside that fancy pencil case glowed the classic yellow highlighter, a staple of any well-respected first grader’s armory. Bolded words stood no chance for 6-year-old Zach’s fantastic highlighting abilities! Textbooks and knowledge, beware! Right?

Well, a review article from 2013 looked at ten learning techniques. They gave the methods a rating of either low, moderate, or high utility based on students’ performance when using those strategies.1

Let’s start with highlighting:

On the basis of the available evidence, we rate highlighting […] as having low utility. In most situations that have been examined and with most participants, highlighting does little to boost performance.

Dunlosky et al.

Goodbye highlighter.

Importantly, for the remainder of the methods discussed and highlighting, this review study looks at many different research studies to come up with their conclusions. They are comparing the results of the ten other study techniques.* In the reviewed studies, highlighting occasionally had significant results compared to nothing. However, highlighting is inferior to other study techniques, such as practice testing and spaced repetition. And not just medium or “so-so,” it’s rated as low utility.

Avoid highlighting at all costs.

2. Underlining

Well, underlining is different, right? Highlighting, maybe I am just using it because I want to see the pretty yellow color. With underlining, it’s more adult, more mature. I would only underline important things. Right? Insert buzzer sound here.

On the basis of available evidence, we rate highlighting and underlining as having low utility.

Dunlosky et al.

Two groups of students were asked to read and understand a text in one study. One group was told to underline themselves, while the other group was given experimenter-generated underlining, so the underlining was done for them.2

Subjects who generated their own underlining did not perform significantly better than those who were given experimenter-generated markings.

Nist & Hogrebe

Darn it! 7-year-old Zach loses again.

3. Summarizing

And you’ll say, wait for a second, Zach, don’t we summarize using the Feynman technique? And I would say “yes” and “no.” Importantly, summarizing can be done without understanding the information you are looking at. I remember, for example, occasionally summarizing a lecture by the title and listing the definition of all the bolded words; that isn’t a summary; that’s poppycock (now, when’s the last time you heard that word?).

The Feynman technique uses self-explanation and elaborative interrogation rated as a medium utility in this review paper. The Feynman technique isn’t just summarizing.

However, summarizing receives the ranking of low utility. According to the researchers, it may benefit those adept at summarizing, but most people are not.1

we rate summarization as low utility. It can be an effective learning strategy for learners who are already skilled at summarizing; however, man learners […] will require extensive training, which makes this strategy less feasible.

Dunlosky et al.

Again, summarizing may be helpful to some, but compared to other study methods, the time spent on summarizing is not worth it.

4. Rereading

I remember my AP psychology class in high school. I thought the only way to prepare for the test was to read and re-read the chapters multiple times until the information stuck in my head. What happened, however, was my mind glazed over. I was flipping pages with nothing sinking into my brain.

The problem with rereading is it’s extremely time-intensive and a form of passive learning.

The relative disadvantage of rereading to other techniques is the largest strike against rereading and is the factor that weighted most heavily in our decision to assign it a rating of low utility.

Dunlosky

The initial reading of the chapter may be helpful, but nothing beyond that. Because I know many of my friends and people watching this video still use rereading, I want to present another journal’s analysis of rereading.3

Basic research on human learning and memory has shown that practicing retrieval of information (by testing the information) has powerful effects on learning and long-term retention. […] Repeating reading […] confers limited benefit beyond that gained from the initial reading of the material.

Karpicke & Roeriger

If you still don’t believe me, I suggest you go to PubMed or google scholar and search “effectiveness of summarizing.”

Rereading is a form of passive learning, stop it and replace it with practice testing; you will save time and score better on your exams.

5. Rewatching or Relistening

Other forms of passive learning include rewatching or relistening; why should these be any different than rereading? They aren’t.

In one study, 102 first-year pharmacy students were tested in lectures after being told to study in two different ways. One way was self-testing, and the other was re-watching lectures. Here is the conclusion of their paper:4

Testing may be more efficient (ie, cost-effective) for long-term performance. Students who attend class may want to avoid rewatching course recordings in favor of practice testing.

Palmer et. al.

However, if you don’t attend lectures, you should still watch the lecture once because that watch will be your first time viewing the material. Rewatching that same lecture, however, is a waste of time.

I did not see evidence for relistening, so this is a Zach hypothesis. But why should it be any different than rewatching or rereading? I almost think it is likely the worst of the three (rereading, rewatching, or relistening) because of how passive it is.

Watch or listen to something once. Don’t rewatch it, don’t relisten to it. Simply eliminating these study strategies can save you about 3x as much time and help you achieve the same or better scores when you switch to active recall techniques.4

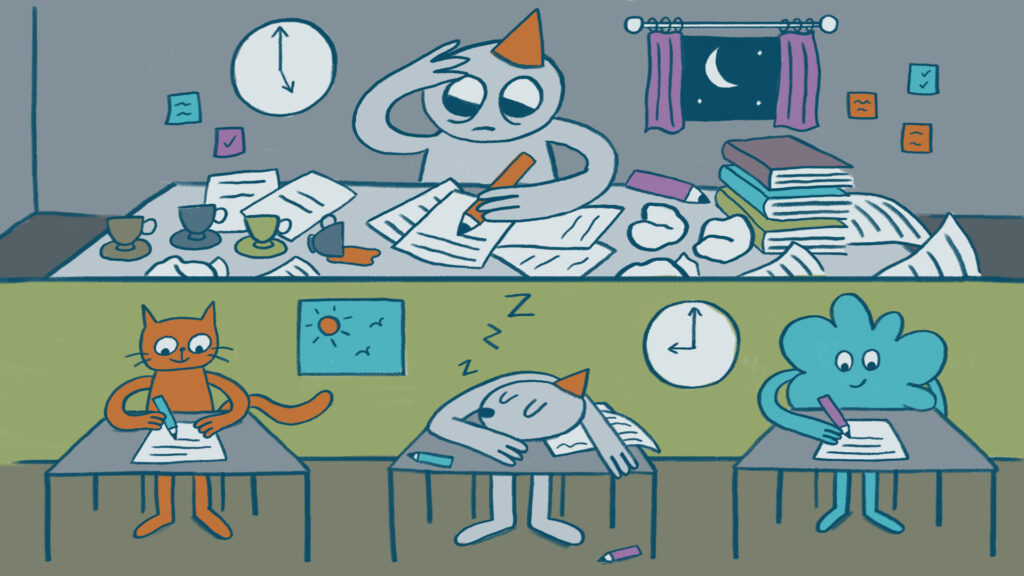

6. All-Nighters

Sleep, proper diet, and exercise. If you don’t have those three things in order, it becomes increasingly difficult to get the other aspects of your life in order. Sleep is the most important of these three.

Sleep is a magical force multiplier to everything you do, your weights in the gym, your happiness levels versus depression, and your ability to study and retain information.5,6

People who sleep and study less vs. those who don’t sleep and study more perform better on exams. Once you go under 7 hours of sleep, your performance and health drop, no matter your age.7

Don’t pull all-nighters. The evidence does not back poor sleep, and an all-nighter the night before an exam will lower your scores.

7. No Plan

Abraham Lincoln famously said,

Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.

Abraham Lincoln

Now, I’m not suggesting sharpening your pencil for four hours; do people even sharpen pencils anymore? Anyway, what I am suggesting is planning what you will study. A huge mistake is showing up at the library with the plan to “study for the test.” Not only will that make you more likely to procrastinate, but you will also lose precious brain power to figure out what to study.

Be as specific as possible with your plans to study; what chapters will you be looking at? How will you be looking at them? Practice questions? Flashcards? How long will you spend on each chapter? How long will you spend in the library?

8. No Breaks

People who take breaks have better cognitive performance.8,9

A new systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of micro-breaks were just published in August of 2022 by a reasonably highly respected journal. In it, they conclude,

Overall, the data support the role of micro-breaks for well-being, while for performance, recovering from highly depleting tasks may need more than a 10-minute breaks.

Albulesco et al.

They also concluded that micro-breaks positively impacted well-being by enhancing vigor and lowering fatigue, regardless of contextual factors.

My favorite method of taking breaks is the Pomodoro method. I study for 25 minutes at a time and then take a 5-minute break. This is repeated four times, and on the fourth time, I take a 30-minute break. Another timing increment I like is 50/10. So 50 minutes of work followed by a 10-minute break. Two cycles and the second cycles break 30 minutes instead of 10.

Overall, limit or eliminate all of the above, and you are well on your way to becoming a better student.

-Zach

*Of note the only “high utility” study strategies were practice testing and distributed practice. Items of medium utility were: elaborative interrogation, self-explanation, and interleaved practice.

Work Cited

- Dunlosky J, Rawson KA, Marsh EJ, Nathan MJ, Willingham DT. Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2013 Jan;14(1):4-58. doi: 10.1177/1529100612453266. PMID: 26173288.

- Nist, S. L., & Hogrebe, M. C. (1987). The role of underlining and annotating in remembering textual information. Reading Research and Instruction, 27(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388078709557922

- Karpicke JD, Butler AC, Roediger HL 3rd. Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practise retrieval when they study on their own?. Memory. 2009;17(4):471‐479. doi:10.1080/09658210802647009

- Palmer S, Chu Y, Persky AM. Comparison of Rewatching Class Recordings versus Retrieval Practice as Post-Lecture Learning Strategies. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019 Nov;83(9):7217. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7217. PMID: 31871348; PMCID: PMC6920633.

- Stickgold, R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature 437, 1272–1278 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04286

- Irit Wolach, Hillel Pratt. The mode of short-term memory encoding as indicated by event-related potentials in a memory scanning task with distractions. Clinical Neurophysiology 112, 186-197 (2001)

- Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker, PhD

- Wanders L, Cuijpers I, Kessels RPC, van de Rest O, Hopman MTE, Thijssen DHJ. Impact of prolonged sitting and physical activity breaks on cognitive performance, perceivable benefits, and cardiometabolic health in overweight/obese adults: The role of meal composition. Clin Nutr. 2021 Apr;40(4):2259-2269. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.006. Epub 2020 Oct 9. PMID: 33873267.

- Albulescu P, Macsinga I, Rusu A, Sulea C, Bodnaru A, Tulbure BT. “Give me a break!” A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of micro-breaks for increasing well-being and performance. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 31;17(8):e0272460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272460. PMID: 36044424; PMCID: PMC9432722.

2 comments

Varoon

Thanks zach i literally have a bundle of thick 200-300 page register full of colorful notes for vast subjects like physics full of beautiful notes but still cant solve elementary physics questions rereading and note taking is the biggest issue no student even knows about i will be happy to see that bundle now as it will remind of these beautiful article written by you and the massive change i had in my learning abilities i only have one question left

is taking rough notes during the lecture effective as i take them only to stay involved in thhe lecture i basically just scribble away data and concepts in a untidy manner so that i have active task on my mind and my mind just doesnt wander away amidst a 2.5 hour lecture i dont think it would waste any time but what are your thoughts?

Zach

I would say 2.5 lecture is a really long lecture. If possible I would split this up into two or three working sessions.

For note taking, I would take MINIMAL notes, and maybe try and do practice problems on the fly with the teacher.

My best experience with lectures is when I prepare the night before for the lecture (by reading the slides, reviewing concepts) and then just being fully present during the lecture, listening, and answering questions.