Remember when you had to learn integrals in math class and had no idea what the F*&# was going on? Why do I have to understand what’s inside of this “S?” What I wish I had known earlier was that there is a better way to learn complex topics.

As a now doctor, I’ve been learning hard stuff for a long time; I’ve been studying university-level material for over 12 years, and not just integrals. Things are even more random, like Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis, or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; who comes up with these names anyway? With some help from academic journals, I discovered the most efficient and effective way to learn complex things quickly, which has changed my life.

We are going to cheat, then read a magazine, then build the house and break the house, and finally meet our friends Jimmy Neutron and Brain Blast before coming back to another dearer (and more real) friend, Richard Feynman.

Here’s how to learn hard stuff, easily.

1. Cheat

How did others learn it? Is there a cheat sheet? You shouldn’t be discovering the theory of relativity on your own here. The best scientists and researchers all develop their theories and discoveries based on others research.

For example, in medical school, many students made their Flashcards in an application called Anki. I know, however, that there was a premade set of cards with all the best information that was collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive (for the most part), allowing me to cover all the information and not waste time.

Another example is video resources and guides, study guides, etc. Don’t be the first person to try and study integrals; there’s a great Khan Academy video on it. Don’t be the first person to try to understand heart failure based on one lecture; there are fantastic Boards and Beyond videos, Osmosis videos, and Amboss resources.

Cheat by taking advantage of the previous students hard work to streamline the basics into your head, what resources to top performers use? In what order? For how long?

2. Magazine It

Look at the title, pretty pictures, exciting bolded words. This is what you do in magazines anyway, right? We want to build our interest in the topic while creating a general layout of what we will learn. If you know a new textbook chapter or lecture slides, briefly glance through the whole thing without trying to understand the content.

- What is the title of the lecture? The chapter titles? The section titles?

- What pictures and graphs are there?

- What are some questions that I am going to be asked based off of this material?

For any day of learning, magazining the material should never take longer than 20 minutes. Remember, it’s a magazine, read it for fun.

3. Build the House

Don’t lie about your knowledge; take a severe analysis of what you understand and don’t understand. As you build your knowledge on this topic, things will only get more difficult as you move on, and a shaky foundation is, well, destructive… house of cards, Kevin Spacey, you know the deal.

How are we going to do this? Well, we just magazine it remember, so now we will understand the Titles, the bolded words, and the section headers in a fundamental way.

Let’s take trying to understand the heart as an example. Before we even begin to think about things like cardiac output or myocytes, we need to understand the building blocks of the heart.

- What is a ventricle? an atrium? What the valves that connect these two? What is the basic function of the heart?

Without understanding the above, there is no basis to learn about different diseases of the heart or difficult cell biology, because we don’t know the point.

Step 1: understand all the bolded words and terms simply by looking them up.

Step 2: create a “one-liner” for the content you are about to learn.

The best way to guide your learning is to develop a “one-liner” of what is going on for the chapter or the basic idea. We do this in medicine multiple times a day, “this is a 60 yo male with a PMH of HTN, smoking, and HLD who presents to the ED with chest pain,” that gives you a pretty fair understanding of what might be going on with this guy right?

So, for a chapter on the heart for example I might say something like this:

The heart’s function is to circulate oxygenated blood throughout the body; it does that by using energy and special muscle cells, cardiac myocytes, to squeeze the deoxygenated blood received in the right atrium to the right ventricle, to the lungs to be oxygenated before returning to the left atrium and then left ventricle where oxygenated blood leaves from and circulates to the rest of the body.

4. Break the House

Split the very difficult thing into it’s core components, and aim to understand each piece over a period of time.

This is where the hard work, hours of studying, and library time come in. However, it still shouldn’t take the majority of time spent studying (that’s the next section), but it should come close. Everything we just did above should take 30 minutes – 1-hour MAX. The above will be part A if you want to be a pro. You do the night before a lecture, then you have your day of lecture (because our brains do well at consolidating and snipping out unnecessary memories while we sleep1,2) and go through steps 4/5/6 after the lecture.

So, for the physiology of the heart (when it’s healthy), for example, this is what I would do:

- Break down the anatomy of the heart, and everything I need to learn about that (right ventricle, valves, blood flow pattern, etc.)

- Understand the Math of the heart and physics (starling curve, cardiac output, etc.)

- Understand the cell biology of the heart (why are cardiac myocytes different? how do they work? How do they all contract in a coordinated fashion?)

So, instead of breaking it into Left Ventricle, Right Ventricle, EKGs, and oxygenated blood, I try to make 3-5 major categories of things I should learn and slowly tick my way through each category by reading the textbook, watching third-party videos, or having an intelligent friend teach me (undervalued).

Next is the top performer from multiple well-respected internet sources. Just like Jimmy Neutron, let’s brain blast!

5. Brain Blast

I will never perfectly understand a topic; I guarantee it. Einstein had many working models of physics that he used to come to the theory of relativity. Mozart had uninteresting and flawed pieces, but he also created moving music; Thomas Edison supposably failed at least over 1,000 times before he made a functional lightbulb.

The point is these notable inventors and scientists didn’t know everything about electricity or gravity before coming to their conclusions and discovering. They tried multiple experiments or problem solutions before coming to an answer.

Here are some facts:

- Students who do problems without seeing the answers perform better on exams and tests than students who simply study the problem-answer combination.5

- Through academic journals and experiments, practice testing is consistently reported as one of the most efficient and effective study techniques for higher grades (compared to highlighting, summarizing, rereading, or underlining).3,4

Simply put, practice testing (a form of active recall) is the highest yield study technique there is.

Now, because of the wide variety of material you could be learning, I’m not going to give specific resources or places to find practice questions or problems, but you know they are there. Generally, you can:

- Look at the back of your textbook

- Ask your teacher for some practice questions

- CREATE some practice questions

- Search online for practice questions

Here’s my guide on properly using practice questions.

6. Feynman Technique

In medicine, we have a phrase: see one, do one, teach one. Now, should we necessarily be teaching something we just learned? Maybe not, but a supervising doctor is always there, watching and correcting mistakes. However, We teach one because this is a fantastic way to learn and solidify the information in our brains.

Evidence shows simply teaching a topic back can dramatically improve retention and memory of a subject as well as exam performance.6,7

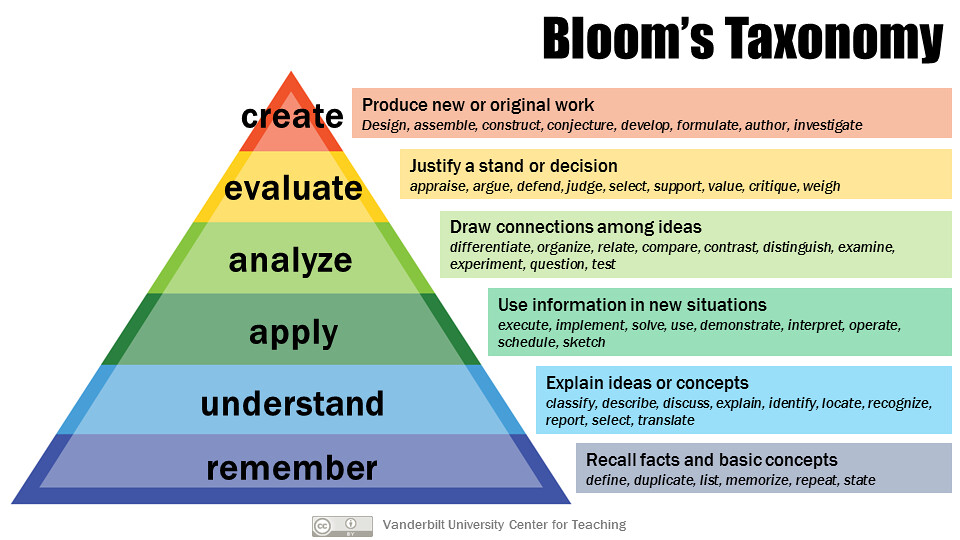

The Feynman technique explains a topic to someone in a simple manor as if you were explaining it to a 12-year-old in your own words. “In your own words” is the most essential part of that definition because it’s how you start to work with the material in your brain. Remember that hierarchy of learning? This gets us to step 4, where we begin to analyze and work with the material, significantly increasing our retention of the material.

The mistake I see most people make: they wait way too long before they start teaching it to someone. I would start trying to teach topics to my friends the next day, or, in medical school, we were forced to introduce a topic to the class the next day. My learning and test scores skyrocketed, likely due to this one intervention.

Here’s my guide on the Feynman Technique.

Summary:

Overall, though, information can be challenging. However, with a well-thought-out strategy, you really can learn anything in the entire world, and this is life-changing. Nothing can stop you; no topic is too complex, and no task is too hard. You are just going to break it down step by step, slowly, and become the powerhouse superstar I know you are. In summary:

- 30 minutes to 1 hour on steps 1-3

- Divide your remaining study time between steps 4 (1/3 of the time) and 5-6 (2/3 of the time) preferably one day after steps 1-3

Good luck, and remember, never get between Carl and a croissant.

Work Cited

- Stickgold, R. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature 437, 1272–1278 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04286

- MacDonald KJ, Cote KA. Contributions of post-learning REM and NREM sleep to memory retrieval. Sleep Med Rev. 2021 Oct;59:101453. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101453. Epub 2021 Jan 23. PMID: 33588273.

- Hartwig MK, Dunlosky J. Study strategies of college students: are self-testing and scheduling related to achievement?. Psychon Bull Rev. 2012;19(1):126‐134. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0181-y

- Dunlosky J, Rawson KA, Marsh EJ, Nathan MJ, Willingham DT. Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2013;14(1):4‐58. doi:10.1177/1529100612453266

- Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

- Dunlosky J, Rawson KA, Marsh EJ, Nathan MJ, Willingham DT. Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2013;14(1):4‐58. doi:10.1177/1529100612453266

- Gregory A, Walker I, Mclaughlin K, Peets AD. Both preparing to teach and teaching positively impact learning outcomes for peer teachers. Med Teach 2011 Aug;33(8):e417-e422.