When the iPhone was released, boredom died along with a part of us. The part that can focus for extended periods of time, the part that comes up with creative ideas, and the part that can be at peace with only our thoughts. In fact, out of all the people who clicked this video, only 50% are still watching because they couldn’t focus for 9 seconds. And within 30 seconds, another 25% of you will click away due to your brain’s addiction to stimulation. But I get it. I’m in the same boat as you. I can’t even watch a 20-minute TV show without looking at my phone, and it’s TV! That is a problem.

Every single time we pick up our phone or turn on the TV to escape boredom, we are obliterating our creativity and focus muscles and building up our stress and addiction muscles.

One meta-analysis looking at over 40,000 children found that those who have problematic smartphone usage (where they would have anxiety or neglect normal activities when the phone was not available) were 2x more likely to be stressed and have poor sleep quality and 3x more likely to have depression and anxiety.1 That brain dopamine parasite feeds on stimulation, and the more it grows, the more it damages us.

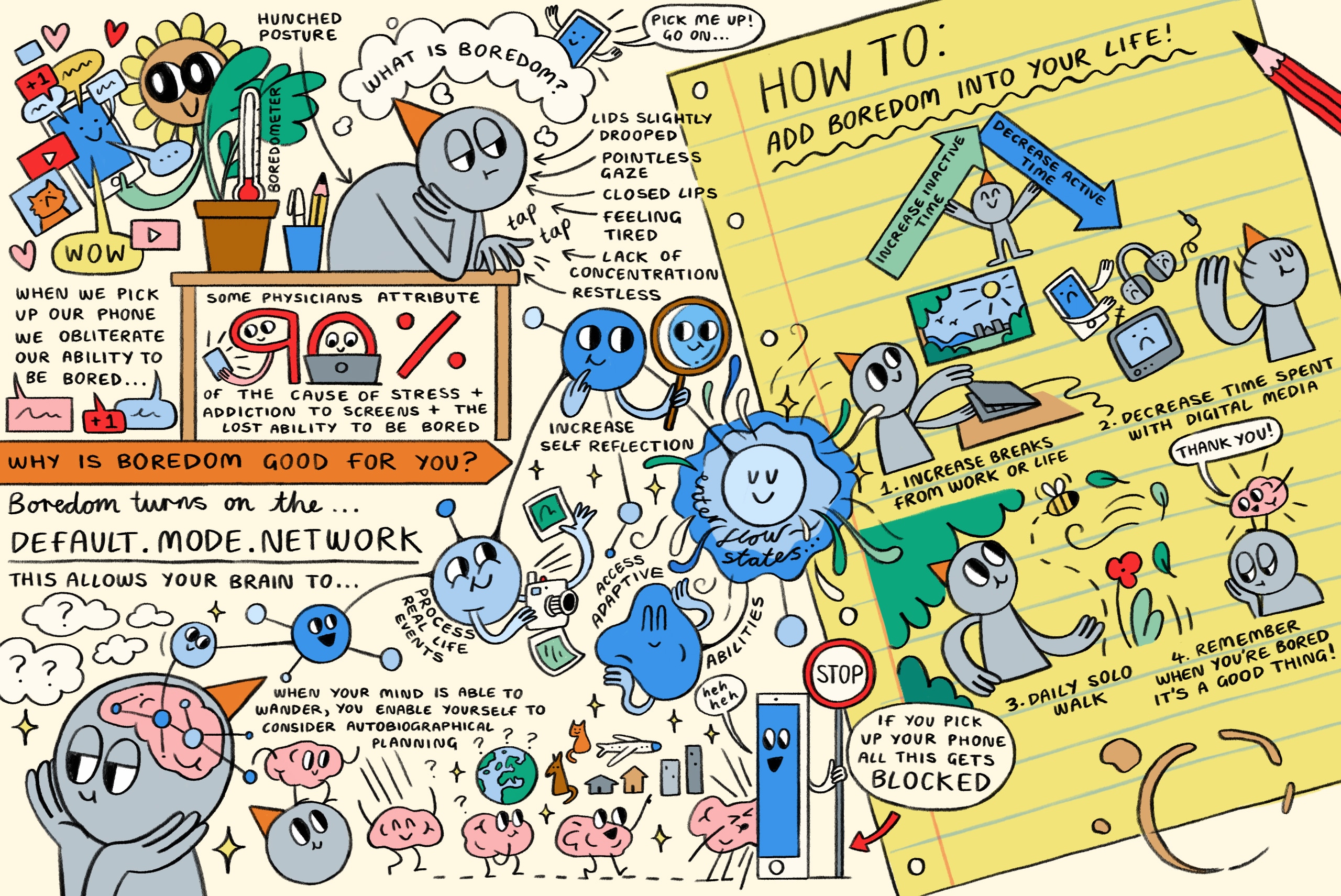

Some psychiatrists even attribute up to 90% of the cause of stress and addiction to screens and our lost ability to be bored.2

The scary part is that the people who are designing these stimulation machines, such as Facebook and TikTok, know they’re a problem. Steve Jobs wouldn’t let his kids use iPads. And Mark Zuckerberg won’t let his kids use Facebook. These people know this technology better than probably anyone else; they made it, so what does it say to us when they ban their children from using it?

So, how do we actually remove this stimulation-hungry parasite that is ruining our brains? Well, the cure is boredom. According to researchers, it’s not picking up the phone that is the problem, but our lost ability to be bored, that is.2 And beyond decreasing our risk of stress, anxiety, depression, and poor sleep, boredom creates improved focus, problem-solving, and self-reflection. 3

What is Boredom?

A group of 4,000 Americans surveyed over 10 days revealed Americans are bored only 2.8% of the time, with 63% reporting being bored at least once during that 10-day period. Amazingly, that means, over 10 days, 37%, or a third of people, never felt bored.

And this makes sense because boredom isn’t fun. Nearly all research points out that people experience boredom as a negative state and try to change the state as fast as possible while also preventing future states of boredom.

But what does being “bored” mean? Is it waiting in line at the coffee shop? Is it stuck in the car or the train? Is it watching a Zach Highley Video? IMPOSSIBLE. Actually, it’s not what most people think. It’s not “having nothing to do,” but psychologists at Texas A&M define it as “The emotional indication to pursue an alternative goal.” Or simply not being satisfied by what you are doing at this moment and searching for something else, characterized by a lack of concentration, restlessness, feeling tired, hunched posture, closed lips, open eyes with the lids slightly drooped, and a pointless gaze.5-7

However, interestingly, those who are bored are not “slower” as those physical attributes may seem to indicate, but faster.

Heart rate and the actual electric potential of your skin increase. Rats that are bored or under-stimulated actually run faster through mazes.8,9 Evidence seems to unilaterally say that the stigma that being in a bored state d is bad is completely wrong.

When was the last time you truly experienced boredom for more than 5 minutes? My guess is it has been a while. From the study above, it seems 1/3rd of people in America simply never experience it. The last time I was bored was when I was sitting on the plane waiting to take off, and my phone died. So I sat there. I twiddled my thumb. I thought of what fun stuff I would do after I landed. I looked through the windows to the greenery outside. If my phone were accessible, it would have been instantly in my hand.

At any moment, we have access to entertainment. But what if boredom is actually the cure to our problems rather than something to avoid? What if when we let our mind wander, it helps us focus, be creative, and design the life of our dreams!

Why is it good for you?

Boredom seems to have two major benefits:

- Activating the default mode network, which turns on creativity and adaptation

- And Improved Autobiographical planning, which plans your life for a change

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a network of brain regions that are active only when we are at rest and not focused on the external environment or completing a task, like daydreaming or mind-wandering, or when the world disappears except for our thoughts. Research says the DMN seems to process real-life events, increase self-reflection, and improve the likelihood of flow states. Not only that, but it’s also apparently critical to our brain’s adaptive abilities. Scarily, those with depression, Alzheimer’s, and schizophrenia more often have a dysfunctional DMN than others.10

Those with a frequently firing DMN are more creative. In one study of 80 people, one group was asked to do boring things to activate the DMN, like copying numbers from a telephone book or watching a Zach Highley video, and another group was asked to do normal stimulating things before both took a creativity test.

The test asked things like, “Think of as many uses for a plastic cup as you can.” Guess what? The “bored” group blew the “stimulated” group out of the water.11 This is amazing to me. It’s like when we give our brain a chance to rest. It gears up and creates new neuronal connections, preparing us to tackle problems and life challenges in completely new ways. For example, I know that I can use a plastic cup as a hat, didn’t think of that one, did you? Yeah, get on my DMN level.

Amazingly, these new thoughts also include potentially redesigning your entire life in the form of “autobiographical planning.”

“Autobiographical planning” is simply life planning. Whenever you are bored, it may be your brain trying to tell you to make a change that is positive for your life. Evolutionarily, this might have meant searching for a new place to forage berries or creating a new hunting tool, but nowadays, we immediately reach for the phone because it’s hacked this feedback loop to block the DMN.

Instead of letting boredom sit and therefore activating our DMN, we instantly reach for quick and easy entertainment, depriving our brains to the longer-term and slower benefits of the DMN. Instant gratification has Hijacked our brains. The average person spends 11 hours and 6 minutes in front of digital media.

In The Comfort Crisis, Michael Easter Says,

The 11 hours and 6 minutes of attention we’re handing over to digital media isn’t free. It’s all spent in focused [non-DMN] mode. Think of this focused state like lifting a weight, and the unfocused [DMN] state like resting. When we kill boredom by burying our minds in a phone, TV, or computer, our brain is putting forth a shocking amount of effort. Like trying to do rep after rep after rep of an exercise, our attention eventually tires when we overwork it.

Modern life overworks the hell out of our brains. Our collective lack of boredom may be causing us to reach near-crisis levels of mental fatigue. Research shows that the onslaught of screen-based media has created Americans who are “increasingly picky, impatient, distracted, and demanding,” as one media analyst put it. These terms fall under the umbrella of “insufferable.” And overworked, undermaintained minds are linked to depression, life dissatisfaction, the perception that life goes by quicker, and increasingly missing the beauty of life that only presents itself when we allow our mind to wander and be aware of something other than a screen.

Finally, Historical leaders knew the importance of preventing boredom and mind-wandering even if they hadn’t named the DMN yet. A political commentator and poet in Roman time, Juvenal, said something like, “Give them bread and circuses, and they will never revolt.” He was criticizing the Roman people’s willingness to not get involved in politics in exchange for the superficial gratification of free food (bread) and entertainment (gladiatorial games and other spectacles or circuses).

On a much smaller scale, this is exactly what I was doing when I was daydreaming on the plane. This current state wasn’t interesting to me, so my body was planning a way to get out of it, which involved doing something not on the plane. Psychologists argue these bored emotions set off a cascade of brain events to help us combat our environmental or internal conditions or problems.

But when we reach for our phone or the TV remote, we don’t give our brain any chance to get to work.3 The argument is that even though this mind-wandering will hurt our performance on the task at hand, like me in English class, the functional body and brain state induced by it will help us achieve more general social and cognitive goals associated with our personally relevant future goals,12 or, “this stuff isn’t good for me, but maybe this other stuff is, and this is how I’m going to do it…” Studies show that those who do this more frequently actually have better working memory, executive function, and overall cognitive performance.12

The good news is your brain is highly malleable, and we can fix it.

How to Add Boredom to Life

Ok, so these scientists have convinced me to subtract some brain-active time from my life and add some brain-inactive DMN time to my life. But how do I actually do this? I’m addicted to my phone. I picked it up 27 times while writing this post and another 33 times while editing this video.

There are only two things to do:

- Decrease active time

- Increase non-active time

Here’s how I’m decreasing active time:

- Integrating more breaks from work or life (10-minute work breaks, hard start and end times to my work)

- Decreasing the amount of time I spend in front of digital media (podcasts, music, phone, TV, movies; I’ve decreased my screen time from 4 hours to 30 minutes a day).

Here’s how I’m increasing my non-active or DMN time

- A daily 10-minute to one-hour solo walk with no phone, preferably in quiet nature (this is game-changing, and evidence supports this will not only help you activate the DMN more but also decrease blood pressure, anxiety, depression, and even your risk for various cardiac and neurological diseases)

- A mindfulness of when I feel bored, and that it’s a good thing. I’ll cook lunch and eat it alone without watching any TV. I’ll lift weights at the gym without music. Or I’ll do some meditation. After doing all this research, I’ve convinced myself, powerfully so, that daydreaming and mind-wandering is a monstrously powerful thing. So, instead of bringing my phone with me to take the dog outside, I leave the phone inside because I know about the DMN. I just walk outside. Instead of playing music in the shower, I just take a shower. Instead of playing a podcast in the car when I drive, I just drive. Instead of pulling out my phone and waiting in line at the grocery store I just look around.

Summary

The inability to be bored has sucked the creativity and happiness from our lives. Luckily, our brains are amazing and can be rewired; they can be fixed. We can reclaim our focus, creativity, and sense of calmness by simply being ok with being bored. Take a step back. Be still. Don’t look at your phone. It’s changed my life. Counterintuitively, the answer to my problems wasn’t adding things to my life but subtracting them. The more I was with myself and the less I was with pings, the happier I was.

The next time you sense your mind wandering on the commute or waiting in line, don’t pick up your phone. Instead, sit in your mind. Be amazed at the thoughts and feelings that suddenly appear in you. Where does your mind go? Break the mold. Be different. Don’t let the algorithms trap you. Boredom isn’t something to fear; it’s the key to unlocking our best ideas and a more fulfilling life.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you weren’t bored. But I do hope you get bored, but, of course, it’s impossible when reading a post from this amazing Zach Highley guy.

Work cited:

- Sohn SY, Rees P, Wildridge B, Kalk NJ, Carter B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2019 Nov 29;19(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2350-x. Erratum in: BMC Psychiatry. 2019 Dec 16;19(1):397. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2393-z. Erratum in: BMC Psychiatry. 2021 Jan 22;21(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02986-2. PMID: 31779637; PMCID: PMC6883663.

- Easter M. The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort to Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self. New York: Rodale Books; 2021.

- Bench SW, Lench HC. On the function of boredom. Behav Sci (Basel). 2013 Aug 15;3(3):459-472. doi: 10.3390/bs3030459. PMID: 25379249; PMCID: PMC4217586.

- Eastwood J.D., Frischen A., Fenske M.J., Smilek D. The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012;7:482–495. doi: 10.1177/1745691612456044.[DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes S. Detecting Boredom in Meetings. University of Twente; Enschede, The Netherlands: 2005. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer K.R., Ellgring H. Multimodal expression of emotion: Affect programs or componential appraisal patterns? Emotion. 2007;7:158–171. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallbott H.G. Bodily expression of emotion. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998;28:879–896. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(1998110)28:6<879::AID-EJSP901>3.0.CO;2-W.[DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London H., Schubert D.S., Washburn D. Increase of autonomic arousal by boredom. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1972;80:29–36. doi: 10.1037/h0033311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler H. Satiation and curiosity: Constructs for a drive and incentive-motivational theory of exploration. Psychol. Learn Motiv. 1967;1:157–227. doi: 10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60514-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V. 20 years of the default mode network: A review and synthesis. Neuron. 2023 Aug 16;111(16):2469-2487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.023. Epub 2023 May 10. PMID: 37167968; PMCID: PMC10524518.

- Mann, S., & Cadman, R. (2014). Does being bored make us more creative? Creativity Research Journal, 26(2), 165-173. DOI: 10.1080/10400419.2014.901073

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053810011001978

2 comments

Amandine

Thank you so much for this inspiring article and your insightful newsletter! I will definitely be intentional about scheduling more “bored time” into my agenda. I’ve always enjoyed allowing myself to do “nothing,” giving my mind the freedom to wander and explore ideas without physical distractions. It truly feels like a form of meditation.

Zach

Hey Amandine! Yes, 10 mins of daily meditation plus a 30-60 min outside walk (with no phone) has changed my life. My best ideas appear out of nowhere now.